Bishop Stephen Bradley observed: “We are in danger of forgetting truths for which previous generations gave their lives.”

That our churches are in danger of forgetting the great Reformation truths, for which previous generations of martyrs willingly laid down their lives, was forcefully impressed upon me during a recent ministry trip to Europe. I had the opportunity to visit Oxford and see the Martyrs Memorial. It drew my attention to an event that occurred 450 years before. The Oxford Martyrs On 16 October 1555, just outside the walls of Balliol College, Oxford, a stout stake had been driven into the ground with faggots of firewood piled high at its base. Two men were led out and fastened to the stake by a single chain bound around both their waists. The older man was Hugh Latimer, the Bishop of Worcester, one of the most powerful preachers of his day, and the other Nicolas Ridley, the Bishop of London, respected as one of the finest theologians in England. More wood was carried and piled up around their feet. Then it was set alight. As the wood kindled and the flames began to rise, Bishop Latimer encouraged his companion: “Be of good cheer, Master Ridley, and play the man! We shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”

Hundreds in the crowd watching the burning of these bishops wept openly.

The place of their execution is marked today by a small stone cross set in the ground in Broad Street, while nearby in St. Giles stands the imposing Martyrs Memorial, erected 300 years later in memory of these two men and of Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who 4 months after their execution suffered the same torturous death by burning, in the same place, and for the same reason. In his trial, Bishop Ridley was urged to reject the Protestant Faith. His reply: “As for the doctrine which I have taught, my conscience assureth me that it is sound, and according to God’s Word…in confirmation thereof I seal the same with my blood.” After much further pressure and torment, Bishop Ridley responded: “So long as the breath is in my body, I will never deny my Lord Christ, and His known truth: God’s will be done in me!” Bishop Latimer declared: “I thank God most heartily, that He hath prolonged my life to this end, that I may in this case glorify God by that kind of death.” Faith and Freedom On one day, in 1519, seven men and women in Coventry were burned alive for teaching their children the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments and the Apostles Creed – in English!

The Illegal English Bible

It may surprise most English-speaking Christians that the first Bible printed in English was illegal and that the Bible translator was burned alive for the crime of translating God’s Word into English. William Tyndale is known as the father of the English Bible, because he produced the first English translation from the original Hebrew and Greek Scriptures. 150 Years earlier Wycliffe had overseen a hand written translation of the Bible, but this had been translated from the Latin Vulgate. Because of the persecution and determined campaign to uncover and burn these Bibles, few copies remain. It would take an average of 8 months to produce a single copy of the Wycliffe Bible, as they had to be written out by hand. William Tyndale’s translation was the first copy of the Scriptures to be printed in the English language. The official Roman Catholic and Holy Roman Empire abhorrence for Bibles translated into the vernacular can be seen from these historic quotes: The Archbishop of Canterbury Arundel declared: “That pestilent and most wretched John Wycliffe, of damnable memory, a child of the old devil, and himself a child and pupil of the anti-Christ…crowned his wickedness by translating the Scriptures into the mother tongue.” Catholic historian Henry Knighton wrote: “John Wycliffe translated the Gospel from Latin into the English…made it the property of the masses and common to all and…even to women…and so the pearl of the Gospel is thrown before swine and trodden under foot and what is meant to be the jewel of the clergy has been turned into the jest of the laity…has become common…” A synod of clergy in 1408 decreed: “It is dangerous…to translate the text of Holy Scripture from one language into another…we decree and ordain that no-one shall in future translate on his authority any text of Scripture into the English tongue or into any other tongue, by way of book, booklet or treatise. Nor shall any man read, in public or in private, this kind of book, booklet or treatise, now recently composed in the time of the said John Wycliffe…under penalty of the greater excommunication.”

God’s Outlaw

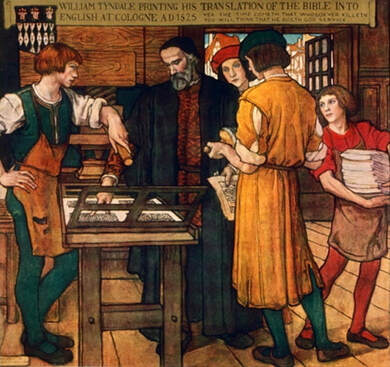

William Tyndale was a gifted scholar, a graduate of both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. It was at Cambridge that Tyndale was introduced to the writings of Luther and Zwingli. Tyndale earned his M.A. at Oxford, then he was ordained into the ministry, served as a chaplain and tutor and dedicated his life to the translation of the Scriptures from the original Hebrew and Greek languages. Tyndale was shocked by the ignorance of the Bible prevalent amongst the clergy. To one such cleric he declared: “I defy the Pope and all his laws. If God spares my life, before many years pass I will make it possible for the boy who drives the plough to know more of the Scriptures than you do.” Failing to obtain any ecclesiastical approval for his proposed translation, Tyndale went into exile to Germany. As he described it “not only was there no room in my lord of London’s palace to translate the New Testament, but also that there was no place to do it in all England.” Supported by some London merchants, Tyndale sailed in 1524 for Germany, never to return to his homeland. In Hamburg he worked on the New Testament, which was ready for printing by the following year. As the pages began to roll off the press in Cologne, soldiers of the Holy Roman Empire raided the printing press. Tyndale fled with as many of the pages as had so far been printed. Only one incomplete copy of this Cologne New Testament edition survives. Tyndale moved to Worms where the complete New Testament was published the following year (1526). Of the 6000 copies printed, only 2 of this edition have survived.

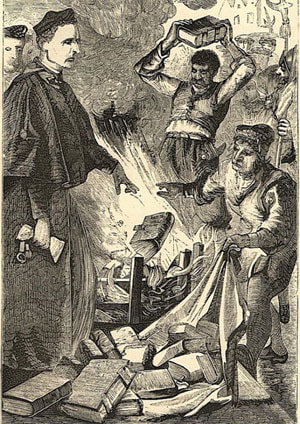

Not only did the first printed edition of the English New Testament need to be produced in Germany, but they had to be smuggled into England. There the bishops did all they could to seek them out and destroy them. The Bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall, preached against the translation of the New Testament into English and had copies of Tyndale’s New Testaments ceremonially burned at St. Paul’s. The Archbishop of Canterbury began a campaign of buying up these contraband copies of the New Testament in order to burn them. As Tyndale remarked, his purchases helped provide the finance for the new improved editions.

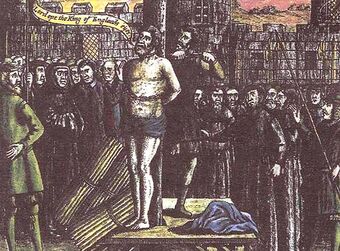

In 1530 Tyndale’s translation of the first five books of the Bible, the Pentateuch (the books of Moses), were printed in Antwerp, Holland. Tyndale continually worked on further revisions and editions of the New Testament. He also wrote The Parable of Wicked Mammon and The Obedience of a Christian Man. This book, The Obedience of a Christian Man, was studied by Queen Anne Boleyn and even found its way to King Henry VIII who was most impressed: “This book is for me and all kings to read!” King Henry VIII sent out his agents to offer Tyndale a high position in his court, a safe return to England and a great salary to oversee his communications. However, Tyndale was not willing to surrender his work as a Bible translator, theologian and preacher merely to become a propagandist for the king! In his book The Practice of Prelates Tyndale argued against divorce and specifically dared to assert that the king should remain faithful to his first wife! Tyndale maintained that Christians always have the duty to obey civil authority, except where loyalty to God is concerned. Henry’s initial enthusiasm for Tyndale turned to rage and so now Tyndale was an outlaw both to the Roman Catholic Church and its Holy Roman Empire, and to the English kingdom. Tyndale also carried out a literary battle with Sir Thomas More, who attacked him in print with Dialogue Concerning Heresies in 1529. Tyndale responded with Answer to More. More responded with Confutation in 1533, and so on. Betrayal and Burning In 1535 Tyndale was betrayed by a fellow Englishman, Henry Phillips, who gained his confidence only to arrange treacherously for his arrest. Tyndale was taken to the state prison in the castle of Vilvorde, near Brussels. For 500 days, Tyndale suffered in a cold, dark and damp dungeon and then on 6 October, 1536, he was taken to a stake where he was garrotted and burned. His last reported words were: “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

Tyndale’s Dying Prayer Answered

The Lord did indeed answer the dying prayer of Tyndale in the most remarkable way. By this time there was an Archbishop of Canterbury (Thomas Cranmer) and a Vicar General (Thomas Cromwell) both of whom were committed to the Protestant cause. They persuaded King Henry to approve the publication of the Coverdale translation. By 1539 every parish church in England was required to make a copy of this English Bible available to all of its parishioners. Miles Coverdale was a friend of Tyndale’s, a fellow Cambridge graduate and Reformer. His edition was the first complete translation of the Bible in English. It consisted mainly of Tyndale’s work supplemented with those portions of the Old Testament which Tyndale had not been able to translate before his death. Then, a year after Tyndale’s death, the Matthews Bible appeared. This was the work of another friend and fellow English Reformer, John Rogers. Because of the danger of producing Bible translations, he used the pen-name Thomas Matthews, which was an inversion of William Tyndale’s initials (WT), ‘TM’. In fact at the end of the Old Testament he had William Tyndale’s initials ‘WT’ printed big and bold. At Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s request, Henry VIII authorised that this Bible be further revised by Coverdale and be called The Great Bible. And so in this way Tyndale’s dying prayer was spectacularly answered. The sudden, unprecedented countrywide access to the Scriptures created widespread excitement. Just in the lifetime of William Shakespeare, 2 million Bibles were sold throughout the British Isles. About 90% of Tyndale’s wording passed on into the King James Version of the Bible.

The Most Influential Englishman

William Tyndale can be described not only as the father of the English Bible, but in a real sense the foremost influence on the shaping of the English language itself. Because Tyndale’s translation was the very first from the original Hebrew and Greek into the English language, he had no previous translations to help in his choice of language. While Latin is noun-rich, Greek and Hebrew are verb-rich. At that time the English language had been heavily influenced by French and Latin. Tyndale went back to the original Saxon and found that Saxon English was more compatible with Greek and Hebrew than with Latin and French. The clarity, simplicity and poetic beauty which Tyndale brought to the English language through his Bible translation served as a linguistic rallying point for the development of the English language. At the time of his translation there were many variations and dialects of English and in many sections of the country the English language was being swamped with French words and Latin concepts. Tyndale’s translation rescued English from these Latin trends and established English as an extension of the Biblical Hebrew and Greek worldview. Thus, every person in the world who writes, speaks, or even thinks, in English, is to a large extent indebted to William Tyndale. It is also extraordinary that while English was one of the minor languages of Europe in the early 16th Century, today it has become a truly worldwide language with over 2 billion people communicating in English. Pioneers for Freedom The Reformation in the 16th Century was one of the most important epochs in the history of the world. The Reformation gave us the Bible – now freely available in our own languages. The now almost universally acknowledged principles of religious freedom, liberty of conscience, the rule of law, the separation of powers and constitutionally limited republics were unthinkable before the Reformation. The Reformers fought for the principles that Scripture alone is our final authority, that Christ alone is the Head of the Church, that salvation is by the grace of God alone, received by faith alone on the basis of the finished work of Christ alone. The Power of the Gospel The Gospel of Christ is life-changing, culture-shaping, history-making and nation-transforming. If it doesn’t change your life, and the lives of those around you, then it’s not the Biblical Gospel.

“All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work.” 2 Timothy 3:16-17

Dr. Peter Hammond This article is adapted from a chapter of The Greatest Century of Reformation, by Dr. Peter Hammond. It is available from Christian Liberty Books, PO Box 358, Howard Place 7450, Cape Town, South Africa, tel: 021-689-7478, email: [email protected]Â and website: www.christianlibertybooks.co.za.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

History ArticlesCategories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

- Home

-

History Articles

- History Articles

- All Categories

- Character Studies

- Greatest Century of Missions

- Greatest Century of Reformation

- Reformation In Bohemia

- Reformation In England

- Reformation In France

- Reformation In Geneva

- Reformation In Germany

- Reformation In Italy

- Reformation In Scotland

- Reformation in Switzerland

- Victorious Christians

- Contemporary Articles

- Resources

- Contact

- Donate

|

The Reformation Society

PO Box 74, Newlands, 7725, South Africa Tel : (021) 689-4480 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2022 ReformationSA.org. All rights reserved |

- Home

-

History Articles

- History Articles

- All Categories

- Character Studies

- Greatest Century of Missions

- Greatest Century of Reformation

- Reformation In Bohemia

- Reformation In England

- Reformation In France

- Reformation In Geneva

- Reformation In Germany

- Reformation In Italy

- Reformation In Scotland

- Reformation in Switzerland

- Victorious Christians

- Contemporary Articles

- Resources

- Contact

- Donate

RSS Feed

RSS Feed