The Reformation in England was quite different to the Reformations in Europe. There was no one dominant individual to give direction to the Reformation in England. Germany had Martin Luther. Switzerland had Ulrich Zwingli. The French-speaking world had John Calvin. But England’s Reformation was very different.

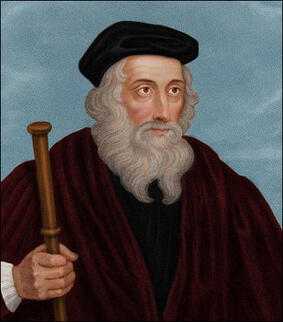

In the 14th Century, Professor John Wycliffe had been the Morning Star of the Reformation. William Tyndale sacrificed his life to provide the first Bible translated from the original Hebrew and Greek and printed into English. But whereas the Reformations in Europe were inspired and directed by religious leaders, the Reformation in England was primarily controlled by political leaders: King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, Queen Elizabeth I and Chancellors such as Thomas Cromwell.

2 Comments

This article is also available as a PowerPoint presentation here. Anne was born during the reign of King Henry VIII to an honoured knight, Sir William Askew. Attractive Anne was described as attractive in form and faith, a beautiful and high-spirited young woman, well educated, with unusual gifts, and “very pious.” Her father arranged that she should be married to the son of a friend, Thomas Kyme, to whom her deceased sister had originally been promised. Faithful Anne endeavoured to be a faithful wife, and bore her husband two children. However, despite an initially happy marriage, her husband, Kyme, threw her out of the home because of her Protestant Faith. Dedicated Anne had acquired a copy of the English Bible and had studied it enthusiastically. She abandoned her formal Catholic religion for the life-changing Protestant Faith in a personal Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ. Her enthusiastic witness drew the attention of the priests who warned her husband about her “sedition.” When challenged she confessed that she was no longer a Romanist, but “a daughter of the Reformation”. At this, her husband threw her out of the home. However, he acknowledged that he had never known a more devout woman than Anne.

In 1513, 22 year old King Henry VIII waged a crusade in Europe on behalf of Pope Julius II, who had promised Henry recognition as a “most Christian King” if he would “utterly exterminate the King of France.” In 1521, Henry authored a book, “The Seven Sacraments” attacking Martin Luther and defending Catholicism’s view of the Sacraments. For this, the Pope gave Henry the title “Defender of The Faith.”

Henry was a Renaissance man, he was fluent in Latin, French and Spanish, an accomplished musician, theologian and Humanist scholar. Yet, despite Henry’s strong loyalties to the Pope, expressed in both blood and ink, Henry did much to open England to the Reformation. It was not so much that Henry embraced the Protestant faith, as much as he came to reject the authority of the Pope over English affairs. Henry was determined to have a male heir to the throne, to protect England from going through the kind of devastating civil war that his father had come to power through (The War of the Roses). Henry ended up going through 6 wives, 2 of whom lost their heads as a result of losing his favour.  Queen Mary is remembered as the ruler who failed to return England to the Catholic Church. As Foxe’s of Martyrs (Acts and Monuments) recorded, not the hundreds of prominent executions carried out under Blood Mary, nor the cruelties, torment, torture and oppression were sufficient to crush the Protestant Reformation in England. In fact, the end result of Mary’s attempts to return England to Catholicism were rather to convince the vast majority of Englishmen in their resolution and determination never to again succumb to such tyranny, superstition, intolerance or error ever again. By trying to exterminate the Reformation, Bloody Mary only succeeded in entrenching it.

Bishop Stephen Bradley observed: “We are in danger of forgetting truths for which previous generations gave their lives.”

That our churches are in danger of forgetting the great Reformation truths, for which previous generations of martyrs willingly laid down their lives, was forcefully impressed upon me during a recent ministry trip to Europe. I had the opportunity to visit Oxford and see the Martyrs Memorial. It drew my attention to an event that occurred 450 years before. The Oxford Martyrs On 16 October 1555, just outside the walls of Balliol College, Oxford, a stout stake had been driven into the ground with faggots of firewood piled high at its base. Two men were led out and fastened to the stake by a single chain bound around both their waists. The older man was Hugh Latimer, the Bishop of Worcester, one of the most powerful preachers of his day, and the other Nicolas Ridley, the Bishop of London, respected as one of the finest theologians in England. More wood was carried and piled up around their feet. Then it was set alight. As the wood kindled and the flames began to rise, Bishop Latimer encouraged his companion: “Be of good cheer, Master Ridley, and play the man! We shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.”  To view the screen capture video of this presentation click here To view the video of this presentation click here To listen to this lecture click here In the 14th Century, Oxford was the most outstanding university in the world and John Wycliffe was its leading Theologian and philosopher. The Black Death (the Bubonic Plague), which killed a third of the population of Europe, led Wycliffe to search the Scriptures and find salvation in Christ. The King’s Champion As a professor at Oxford University, Wycliffe represented England in a controversy with the pope. Wycliffe championed the independence of England from Papal control. He supported King Edward III’s refusal to pay taxes to the pope. (It was only one step away from denying the political supremacy of the pope over nations to questioning his spiritual supremacy over churches). The royal favour which Wycliffe earned from this confrontation protected him later in life.

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) was one of the greatest leaders ever to rule England. He was a dedicated Puritan, deeply and fervently devoted to carrying out the will of God. He was relentless in battle, brilliant in organization and had a genius for cavalry warfare. With a Psalm on his lips and a sword in his hand he led his Ironsides to victory after victory, first against the Royalists in England, then against the Catholics of Ireland, and finally against the rebellious Scots.

Oliver Cromwell pursued religious toleration which helped to stabilize the fragile country after the King was executed. His foreign policy in support of beleaguered Protestants in Europe and against Muslim pirates in the Mediterranean was successful and he restored the supremacy of the seas to England. |

History ArticlesCategories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

- Home

-

History Articles

- History Articles

- All Categories

- Character Studies

- Greatest Century of Missions

- Greatest Century of Reformation

- Reformation In Bohemia

- Reformation In England

- Reformation In France

- Reformation In Geneva

- Reformation In Germany

- Reformation In Italy

- Reformation In Scotland

- Reformation in Switzerland

- Victorious Christians

- Contemporary Articles

- Resources

- Contact

- Donate

|

The Reformation Society

PO Box 74, Newlands, 7725, South Africa Tel : (021) 689-4480 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2022 ReformationSA.org. All rights reserved |

- Home

-

History Articles

- History Articles

- All Categories

- Character Studies

- Greatest Century of Missions

- Greatest Century of Reformation

- Reformation In Bohemia

- Reformation In England

- Reformation In France

- Reformation In Geneva

- Reformation In Germany

- Reformation In Italy

- Reformation In Scotland

- Reformation in Switzerland

- Victorious Christians

- Contemporary Articles

- Resources

- Contact

- Donate

RSS Feed

RSS Feed