The Controversial

Luther has been alternatively described as the brilliant scholar who rediscovered the central message of the Bible, a prophet like Elijah and John the Baptist to reform God’s people, the liberator who arose to free his people from the oppression of Rome, the last medieval man, and the first modern man. Zwingli described him as: “the Hercules who defeated the tyranny of Rome.” Pope Leo X called Luther: “A wild boar, ravaging his vineyard.” Emperor Charles V described him as: “A demon in the habit of a monk!” The Son Martin Luther was born 10 November 1483 in Eisleben, Saxony. His father, Hans Luder, had worked hard to climb the “social ladder” from his humble peasant origins to become a successful copper mining entrepreneur. Hans married Margaretha Lindemann, the daughter of a prosperous and gifted family that included doctors, lawyers, university professors and politicians. Hans Luder owned several mines and smelters and he became a member of the City Council in Mansfield, where Martin was raised, under the strict discipline typical of that time.

The Student

From age 7, Martin began studying Latin at school. Hans intended his son to become a lawyer, so he was sent on to the University of Erfurt before his 14th birthday. Martin proved to be extraordinarily intelligent and he earned his BA and MA degrees in the shortest time allowed by the statutes of the University. Martin proved so effective in debating, that he earned the nickname: “the philosopher.” The Storm As Martin excelled in his studies, he began to be concerned about the state of his soul and the suitability of the career his father had set before him. While travelling on foot, near the town of Stotternhein, a violent thunderstorm brought Martin to his knees. With lightning striking all around him, Luther cried out for protection to the patron saint of miners: “St. Anne, help me, I will become a monk!” The storm around him matched the conflict raging within his soul.

The Monk

Although his parents were pious people, they were shocked when he abandoned his legal studies at Erfurt and entered the Augustinian monastery. Martin was 21 years old when, in July 1505, he gave away all his possessions – including his lute, his many books and clothing – and entered the Black Cloister of the Augustinians. Luther quickly adapted to monastic life, throwing himself wholeheartedly into the manual labour, spiritual disciplines and studies required. He went way beyond the fasts, prayers and ascetic practices required and forced himself to sleep on the cold stone floor without a blanket, whipped himself, and seriously damaged his health. He was described as: “devout, earnest, relentlessly self-disciplined, unsparingly self-critical, intelligent…” and “impeccable.” Luther rigorously pursued the monastic ideal and devoted himself to study, prayer and the sacraments. He wearied his priest with his confessions and with his punishments of himself with fasting, sleepless nights, and flagellation. The Professor Luther’s wise and godly superior, Johannes von Staupitz, recognised Martin’s great intellectual talents, and to channel his energies away from excessive introspection ordered him to undertake further studies, including Hebrew, Greek and the Scriptures, to become a university lecturer for the order. Luther was ordained a priest in 1507 and studied and taught at the Universities of Wittenberg and Erfurt (1508 – 1511). In 1512, Martin Luther received his doctoral degree and took the traditional vow on becoming a professor at Wittenberg University to teach and defend the Scriptures faithfully. This vow would be a tremendous source of encouragement to him later. Luther never viewed himself as a rebel, but rather as a theologian seeking to be faithful to the vow required of him to teach and defend Holy Scripture. Luther committed most of the New Testament, much of the Old Testament and all of the Psalms to memory.

Wittenberg

The University of Wittenberg had been founded by Prince Frederick of Saxony in 1502. Luther’s friend from his university days in Erfurt, George Spalatin, was now chaplain and secretary to the Prince, and closely involved in the Prince’s pet project of his new university. Wittenberg at this time was a small river town with only about 2,000 residents. Prince Frederick wanted to build it up into his new capital of Saxony. Studies That Shook the World From 1513 to 1517, Luther lectured at the University on the Psalms, Romans and Galatians. Being a university professor would have been a full-time job; however, Luther had other responsibilities as well. He was the supervisor for 11 Augustinian monasteries, including the one at Wittenberg. Luther was also responsible for preaching regularly at the monastery chapel, the town church and the castle church. It was a combination of Luther’s theological and pastoral concerns that led him to take the actions that sparked the Reformation. Luther had long been troubled spiritually with the righteousness of God. God demanded absolute righteousness: “Be perfect, even as your Father in Heaven is perfect.” “Be holy, as I am Holy.” We are obligated to love God whole-heartedly, and our neighbours as ourselves. It was because of his great concern for his eternal salvation that Luther had sought to flee the world. In spite of the bitter grief and anger of his father, he had buried himself in the cloister and devoted himself to a life of the strictest asceticism. Yet, despite devoting himself to earning salvation by good works, cheerfully performing the humblest tasks, praying, fasting, chastising himself even beyond the strictest monastic rules, he was still oppressed with a terrible sense of his utter sinfulness and lost condition.

“The Just Shall Live By Faith”

Then Luther found some comfort in the devotional writings of Bernard of Clairvoux, who stressed the free grace of Christ for salvation. The writings of Augustine provided further light. Then, as he begun to study the Scriptures, in the original Hebrew and Greek, joy unspeakable flooded his heart. It was 1512, as he began to study Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, that the verse “For in the Gospel a righteousness from God is revealed, a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: the righteous will live by faith” Romans 1:17 Luther later testified that as he began to understand that this righteousness of God is a free gift by God’s grace through which we may live by faith, “I felt entirely born again and was led through open gates into Paradise itself. Suddenly the whole of Scripture had a different appearance for me. I recounted the passages which I had memorised and realised that other passages, too, showed that the work of God is what God works in us… thus St. Paul’s words that the just shall live by faith, did indeed become to me the gateway to Paradise.” The burden of his sin rolled away. Up until then, Luther had tried to earn salvation by his good works, although he never felt that he had been able to do enough. Now, God had spoken to him through the Scripture. Man is not saved by works, but by faith alone.

A Turning Point

As a doctor, Luther had taken an oath to serve the Church faithfully by the study and teaching of Holy Scripture. At the university, he was responsible to prepare pastors. Now, having experienced God’s grace in Christ, studying God’s Word, Luther began to see the emptiness, self-absorption, pious pretence and superstitious unbelief of his previous religious devotion. Nor could Luther fail to recognise the same pious fraud and pharisaic futility all around him. In 1510, before being made a professor at Wittenberg, Luther had been sent to Rome for his monastic order. What he had seen there had shocked and disillusioned him. Rome was the pre-eminent symbol of ancient civilisation and “the residence of Christ’s Vicar on earth” the pope. Luther was horrified by the blatant immorality and degeneracy prevalent in Rome at that time. Understanding Catholicism The centre of medieval Roman Catholic church life was the Mass, the Sacrament of the altar. The Roman Catholic institution placed much emphasis on the punishment of sin in Purgatory, as a place of cleansing by fire before the faithful were deemed fit to enter Heaven. They taught that there were four sacraments that dealt with the forgiveness, and the removal of sin, and the cancellation of its punishment: Baptism, The Mass, Penance and Extreme Unction. The heart of Penance was the priestly act of Absolution whereby the priest pardoned the sins and released the penitent from eternal punishment. Upon the words of Absolution, pronounced by the priest, the penitent sinner received the forgiveness of sins, release from eternal punishment and restoration to a state of grace. This would require the sinner making some satisfaction, by saying a prescribed number of prayers, by fasting, by giving alms, by going on a pilgrimage, or by taking part in a crusade. Indulgences In time, the medieval church had come to allow the penitent to substitute the payment of a sum of money for other forms of penalty or satisfaction. The priest could then issue an official statement, an indulgence, declaring the release from other penalties through the payment of money. In time, the Catholic church came to allow indulgences to be bought, not only for oneself, but also for relatives and friends who had died and passed into Purgatory. They claimed that these indulgences would shorten the time that would otherwise have to be spent suffering in Purgatory. This practice of granting indulgences was based upon the Catholic doctrine of Works of Supererogation. This unbiblical doctrine claimed that works done beyond the demands of God’s Law earned a reward. As Christ and the saints had perfected Holiness and laid up a rich treasury of merits in Heaven, the Roman church claimed that it could draw upon this treasury of “extra merits” to provide satisfaction for those who paid a specified sum to the church.

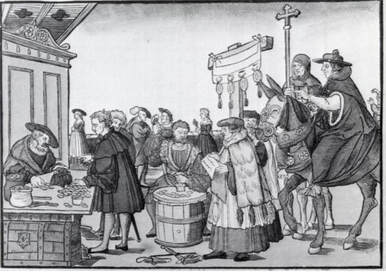

The Indulgence Industry

This system of indulgences was very popular with the masses of people who preferred to pay a sum of money to saying many prayers and partaking in many masses to shorten the suffering in Purgatory of either themselves or a loved one. The industry of indulgences had also become a tremendous source of income for the Papacy. In order to fund the building of the magnificent St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, Pope Leo X had authorised a plenary, or total indulgence. And so it was on this papal fundraising campaign to complete the construction of St. Peters Basilica that the Dominican monk and indulgence salesman extraordinary, John Tetzel, arrived in Saxony. The shameless and scandalous manner in which Tetzel hawked the indulgences outraged Martin Luther. Sales jingles such as: “As soon as the coin clinks in the chest, a soul flies up to Heavenly rest” were deceiving gullible people about their eternal souls. Luther’s study of the Scripture had convinced him that salvation came by the grace of God alone, based upon the atonement of Christ on the cross alone, received by faith alone. Indulgences could not remove any guilt, and could only induce a false sense of security. People were being deceived for eternity.

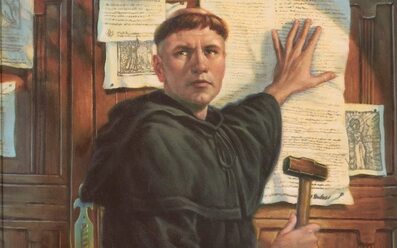

The 95 Theses

Concerns that had been growing since his visit to Rome in 1510 led Luther now to make a formal objection to the abuses of indulgences. On All Saint’s Day (1 November), people would be coming from far and wide in order to view the more than 5,000 relics exhibited in the Schlosskirche, which had been built specifically for the purpose of housing this massive collection. So, on 31 October 1517, Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses against indulgences on to the door of the castle church. He also posted a copy to the Archbishop of Mainz. These Theses created such a sensation that within 2 weeks, they had been printed and read throughout Germany. Within the month, translations were being printed and sold all over Europe. The 95 Theses begin with the words: “Since our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ says: ‘Repent, for the Kingdom of Heaven is near’ (Matthew 4:17), He wants the whole life of a believer to be a life of Repentance.” Luther maintained that no sacrament can take away our responsibility to respond to Christ’s command by an inner repentance evidenced by an outward change, a transformation and renewal of our entire life. Luther emphasised that it is God alone who can forgive sins and that indulgences are a fraud. It would be far better to give to the poor, than to waste one’s money on indulgences. If the Pope really had power over the souls suffering in Purgatory, why would he not release them out of pure Christian charity?

The Empire Strikes Back

Luther’s 95 Theses radically undermined Tetzel’s business, almost bringing the sale of indulgences to a standstill. Tetzel, Mazzolini, and John Eck published attacks on Luther, defending the sale of indulgences. When none of Luther’s friends rose to his defence, Luther felt deserted. Many of his closest friends believed that he had been too rash in his criticism of this established church practice. With the pope’s power challenged and papal profits eroded, church officials mobilised their forces to bring this rebellious professor into line. First the Augustinians at their regular meeting in Heidelberg sought to silence Luther. Then he underwent three excruciating interviews with Cardinal Cajetan in Augsburg. Then in June 1519, John Eck debated Luther in Leipzig. Some close friends of Luther tried to persuade him to settle things peacefully by giving in, but to Luther this was now a matter of principle. Scriptural truth and eternal souls were at stake. In preparation of the Leipzig debate, Luther had plunged into the study of church history and canon law. His studies convinced Luther that many of the decretals, such as the donation of Constantine, were forgeries. The Leipzig Debate On 4 July 1519, Eck and Luther faced one another in Leipzig. The issue being debated was the supremacy of the Pope. Luther pointed out that the Eastern Greek Church was part of the Church of Christ, even though it had never acknowledged the supremacy of the Bishop in Rome. The great Church Councils of Nicea, Chalcedon and Ephesus knew nothing of papal supremacy. But Eck maneuvered Luther into a corner and provoked him to defend some of the teachings of (condemned heretic) John Hus. By making Luther openly take a stand on the side of a man official condemned by the church as a heretic, Eck was convinced that he had won the debate. However, Luther greatly strengthened his cause amongst his followers, winning many new supporters, including Martin Bucer, (who became a crucial leader of the Reformation, even helping to disciple John Calvin). Luther published an account of the Leipzig debate and followed this up with an abundance of teaching pamphlets. “On Good Works” had a far-reaching effect teaching that man is saved by faith alone. “The noblest of all good works is to believe in Jesus Christ.” Luther maintained: that shoemakers, housekeepers, farmers and businessmen, if they do their work to the glory of God, are more pleasing to God than monks and nuns.

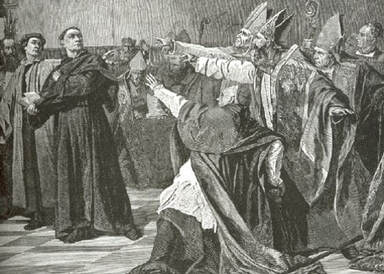

Excommunication

On 15 June 1520, Pope Leo X signed the Bull excommunicating Luther. Describing Luther’s teaching as: “heretical,” “scandalous,” “false,” “offensive” and “seducing,” the Bull called upon all Christians to burn Luther’s books and forbid Luther to preach. All towns or districts that sheltered him would be placed under an interdict. In response, Luther wrote: “Against the Execrable Bull of AntiChrist.” On 10 December 1520, surrounded by a large crowd of students and lecturers, he burned the Papal bull, along with books of canon law, outside the walls of Wittenberg. Having exhausted all ecclesiastical means to bring Luther to heel, Pope Leo now appealed to the Emperor to deal with Luther. Summoned to Worms Previously, in 1518, when the Pope had summoned Luther to Rome, Prince Frederick had brought all his influence to have this Papal summons cancelled. When Luther had been summoned to Augsburg and Leipzig, Prince Fredrick had arranged for safe conduct guarantees. But now that the Emperor Maximilian had died, Charles V of Spain had been elected Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Prince Frederick himself had been a serious contender for this position and still held tremendous influence. So he prevailed upon Charles V to guarantee safe conduct for Luther as he was summoned to Worms for a Council of German rulers.

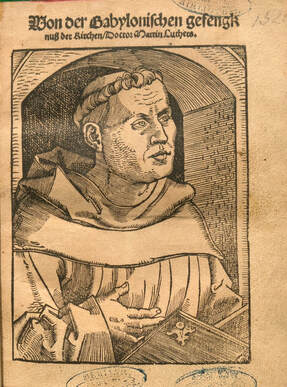

The State

In the year before his summons to the Diet of Worms, Luther published some of his most powerful and influential treatises. In the Address to the German Nobility (August 1520) he called on the Princes to correct the abuses within the church and to free the German church from the exploitation of Rome. The Church In The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (October 1520), Luther argued that Rome’s sacramental system held Christians captive. He attacked the papacy for depriving individual Christians of their freedom to approach God directly by faith – without the mediation of unbiblical priests and sacraments. To be valid, a sacrament had to be instituted by Christ and be exclusively Christian. By these tests, he could find no justification for five of the Roman Catholic sacraments. Luther retained only Baptism and The Lord’s Supper and placed these within the community of believers, rather than in the hands of a church hierarchy. Indeed, Luther dismissed the traditional view of the church as the sacred hierarchy headed by the Pope and presented the Biblical view of the Church as a community of the regenerate in which all believers are priests, having direct access to God through Christ.

The Christian Life

In The Liberty of a Christian Man (November 1520), Luther presented the essentials of Christian belief and behaviour. Luther removed the necessity of monasticism by stressing that the essence of Christian living lies in serving God in our calling, whether secular or ecclesiastical. In promoting this Protestant Work Ethic, Luther laid the foundation for free enterprise and the tremendous productivity it has inspired. He taught that good works do not make a man good, but a good man does good works. Fruit does not produce a tree, but a tree does produce fruit. We are not saved by doing good works, but by grace alone. However, once saved, we should expect good works to flow as the fruit of true faith. Facing Certain Death Summoned to Worms, Luther believed that he was going to his death. He insisted that his co-worker, Philip Melanchthon, remain in Wittenberg. “My dear brother, if I do not come back, if my enemies put me to death, you will go on teaching and standing fast in the truth; if you live, my death will matter little.” Luther at Worms was 37 years old. He had been excommunicated by the Pope. Luther would have remembered that the Martyr, John Hus, a century before had travelled to Constance with an imperial safe conduct, which was not honoured. Luther declared: “Though Hus was burned, the truth was not burned, and Christ still lives… I shall go to Worms, though there be as many devils there as tiles on the roofs.” Luther’s journey to Worms was like a victory parade. Crowds lined the roads cheering the man who had dared to stand up for Germany against the Pope.

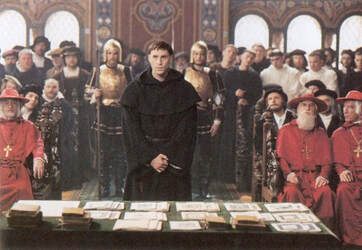

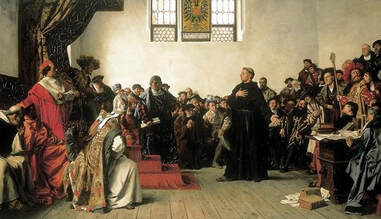

Before the Emperor

At 4 o’ clock on Wednesday 17 April, Luther stood before the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire. Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled all the Austrian domains, Spain, Netherlands, a large part of Italy and the Americas. At 21 years old, Charles V ruled over a territory larger than any man since Charlemagne. Amidst the pomp and splendour of this imperial gathering stood the throne of the Emperor on a raised platform. It was flanked by Spanish knights in gleaming armour, 6 Princes, 24 Dukes, 30 Archbishops and Bishops, and 7 Ambassadors. Luther was asked to identify whether the books on the table were his writings. Upon Luther’s confirmation that they were, an official asked Luther: “Do you wish to retract them, or do you adhere to them and continue to assert them?” Luther had come expecting an opportunity to debate the issues, but it was made clear to him that no debate was to be tolerated. The Imperial Diet was ordering him to recant all his writings. Luther requested more time, so that he might answer the question without injury to the Word of God and without peril to his soul. The Emperor granted him 24 hours. Confrontation The next day, Thursday 18 April, as the sun was setting and torches were being lit, Luther was ushered into the august assembly. He was asked again whether he would recant what he had written. Luther responded that some of his books taught established Christian doctrine on faith and good works. He could not deny accepted Christian doctrines. Other of his books attacked the papacy and to retract these would be to encourage tyranny and cover up evil. In the third category of books, he had responded to individuals who were defending popery and in these Luther admitted he had written too harshly. The examiner was not satisfied: “You must give a simple, clear and proper answer… will you recant or not?”

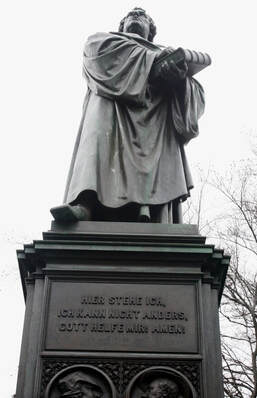

“Here I Stand”

Luther’s response, first given in Latin and then repeated in German, shook the world: “Unless I am convinced by Scripture or by clear reasoning that I am in error – for popes and councils have often erred and contradicted themselves – I cannot recant, for I am subject to the Scriptures I have quoted; my conscience is captive to the Word of God. It is unsafe and dangerous to do anything against one’s conscience. Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. So help me God. Amen.” After the shocked silence, cheers rang out for this courageous man who had stood up to the Emperor and the Pope. Luther turned and left the tribunal. Numerous German nobles formed a circle around Luther and escorted him safely back to his lodgings. Condemned The Emperor was furious. However, Prince Frederick insisted that Charles V honour the guarantee of safe conduct for Luther. Charles V raged against “this devil in the habit of a monk” and issued the edict of Worms, which declared Luther an outlaw, ordering his arrest and death as a “heretic.”

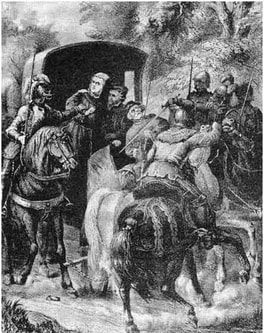

Kidnapped

As Luther travelled back to Wittenberg, preaching at towns along the route, armed horsemen plunged out of the forest, snatched Luther from his wagon and dragged him off to Wartburg Castle. This kidnapping had been arranged by Prince Frederick amidst great secrecy in order to preserve Luther’s life. Despite the Emperor’s decree that anyone helping Luther was subject to the loss of life and property, Frederick risked his throne and life to protect his pastor and professor. Wartburg Castle For the 10 months that Luther was hidden at Wartburg Castle, as Knight George (Junker Jorg), he translated The New Testament into German and wrote such booklets as: “On Confession Whether the Pope Has the Authority to Require It; On the Abolition of Private Masses” and “Monastic Vows.” By 1522, The New Testament in German was on sale for but a week’s wages. Revolution Rebuked In Luther’s absence, Professor Andreas Karlstadt instituted revolutionary changes, which led to growing social unrest. In March 1522, Luther returned to Wittenberg, and in 8 days of intensive preaching, renounced many of Karlstadt’s innovations, declaring that he was placing too much emphasis on external reforms and introducing a new legalism that threatened to overshadow justification by faith and the spirituality of the Gospel. Luther feared that the new legalism being introduced would undermine the Reformed movement from within.

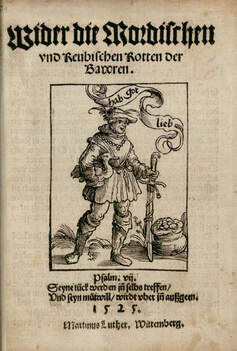

The Peasants’ Revolt

When the peasants’ revolt erupted, Luther was horrified at the anarchy, chaos and bloodshed. He repudiated the revolutionaries and wrote “Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants.” Aghast at the devastation and massacres caused by the peasants’ revolt, Luther taught that the princes had the duty to restore social order and crush the insurrection. Marriage Also in 1525, on 13 June, Luther married Katherine von Bora, a former nun from a noble family. Luther called home life: “the school of character” and he stressed the importance of the family as the basic building block of society. Luther and Katie were blessed with 6 children. The Bondage of the Will Also in 1525, Luther wrote one of his most important books: “On the Bondage of the Will.” This was in response to Desiderius Erasmus’s book on The Freedom of The Will, published in 1524. Luther responded scathingly to Erasmus’s theories on free will, arguing that man’s will is so utterly in bondage to sin, that only God’s action could save. Luther articulated the Augustinian view of predestination and declared that he much preferred that his salvation be in God’s Hands, rather than in his own. As a result of the exchange between Luther and Erasmus, many Renaissance Humanist scholars ceased to support Luther.

A Time of Change

The Reformation not only brought about sweeping changes in the church, but dramatic changes in all of society. First of all the Reformation focused on bringing doctrines, forms of church government, and of worship and daily life into conformity with the Word of God. This, of course, had tremendous implications for political, economic, social and cultural life as well. God’s Word Above All Things Luther revised the Latin liturgy and translated it into German. Now the laity received the Communion in both bread and wine, as the Hussites had taught a Century earlier. The whole emphasis in church services changed from the sacramental celebration of the Mass as a sacrifice to the preaching and teaching of God’s Word. Luther maintained that every person has the right and duty to read and study the Bible in his own language. This became the foundation of the Reformation: a careful study of the Bible as the source of all truth and as the only legitimate authority, for all questions of faith and conduct. The True Church The Church is a community of believers, not a hierarchy of officials. The Church is an organism rather than an organisation, a living body of which each believer is a member. Luther stressed the priesthood of all believers. We do not gain salvation through the church, but we become members of the Church when we become believers. Reformation Basic PrinciplesLuther dealt with many primary issues, including:

The Battle Cries of The ReformationThe Protestant Reformation mobilised by Luther rallied around these great battle cries:

Surviving as an Outlaw Despite Luther being declared an outlaw by the Emperor, he survived to minister and write for 25 more years, and died of natural causes, 18 February 1546. Translator, Author and Musician In spite of many illnesses, Luther remained very active and productive as an advisor to princes, theologians and pastors, publishing major commentaries, and producing great quantities of books and pamphlets. He completed the translation of the Old Testament into German by 1534. Luther continued preaching and teaching to the end of his life. He frequently entertained students and guests in his home, and he produced beautiful poems and hymns, including one hymn that will live forever: “Ein Feste Burg Ist Unser Gott” (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God). Teacher Luther also did a great deal to promote education. He laboured tirelessly for the establishment of schools everywhere. Luther wrote his Shorter Catechism in order to train up children in the essential doctrines of the faith.

An Exceptional Professor

It has been common to portray Luther as a simple and obscure monk, who challenged the pope and emperor. Actually Luther was anything but simple or obscure. He was learned, experienced and accomplished far beyond most men of his age. He had lived in Magdeburg and Eisenach and was one of the most distinguished graduates of the University of Erfurt. Luther travelled to Cologne, to Leipzig, and he had crossed the Alps and travelled to Rome. Luther was a great student, with a tremendous breadth of reading, who had excelled in his studies, and achieved a Master of Arts and Doctorate in Theology in record time. He was an accomplished bestselling author, one of the greatest preachers of all time, a highly respected Theological professor, and one of the first professors to lecture in the German language, instead of in Latin. Productive and Influential Far from being a simple monk, Luther was the Prior of his monastery and the district vicar over 11 other monasteries. Luther was a monk, a priest, a preacher, a professor, a writer, and a Reformer. He was one of most courageous and influential people in all of history. The Lutheran Faith was adopted not only in Northern Germany, but also throughout Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland. Luther Changed the World Luther was a controversial figure in his day and has continued to be considered controversial to this very day. There is no doubt that Luther’s search for peace with God changed the whole course of human history. He challenged the power of Rome over the Christian Church, smashed the chains of superstition and tyranny and restored the Christian liberty to worship God in spirit and in truth. “For I am not ashamed of the Gospel of Christ, for it is the power of God to salvation for everyone who believes …For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith; as it is written, the just shall live by faith.” Romans 1:16-23

This article is adapted from a chapter of The Greatest Century of Reformation,

by Dr. Peter Hammond. It is available from Christian Liberty Books, PO Box 358, Howard Place 7450, Cape Town, South Africa, tel: 021-689-7478, email: [email protected] and website: www.christianlibertybooks.co.za. The Reformation Society P.O. Box 74 Newlands 7725 Cape Town South Africa Tel: 021-689-4480 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ReformationSA.org Website: www.Reform500.org See also: The Reformation Roots of Western Civilisation A Bold New Initiative for Reformation Today Reformation FIRE for Africa

1 Comment

William Mulligan

2/21/2023 11:23:13 am

Very enlightening and easy to read. Thankyou

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

History ArticlesCategories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

- Home

-

History Articles

- History Articles

- All Categories

- Character Studies

- Greatest Century of Missions

- Greatest Century of Reformation

- Reformation In Bohemia

- Reformation In England

- Reformation In France

- Reformation In Geneva

- Reformation In Germany

- Reformation In Italy

- Reformation In Scotland

- Reformation in Switzerland

- Victorious Christians

- Contemporary Articles

- Resources

- Contact

- Donate

|

The Reformation Society

PO Box 74, Newlands, 7725, South Africa Tel : (021) 689-4480 Email: [email protected] Copyright © 2022 ReformationSA.org. All rights reserved |

- Home

-

History Articles

- History Articles

- All Categories

- Character Studies

- Greatest Century of Missions

- Greatest Century of Reformation

- Reformation In Bohemia

- Reformation In England

- Reformation In France

- Reformation In Geneva

- Reformation In Germany

- Reformation In Italy

- Reformation In Scotland

- Reformation in Switzerland

- Victorious Christians

- Contemporary Articles

- Resources

- Contact

- Donate

RSS Feed

RSS Feed